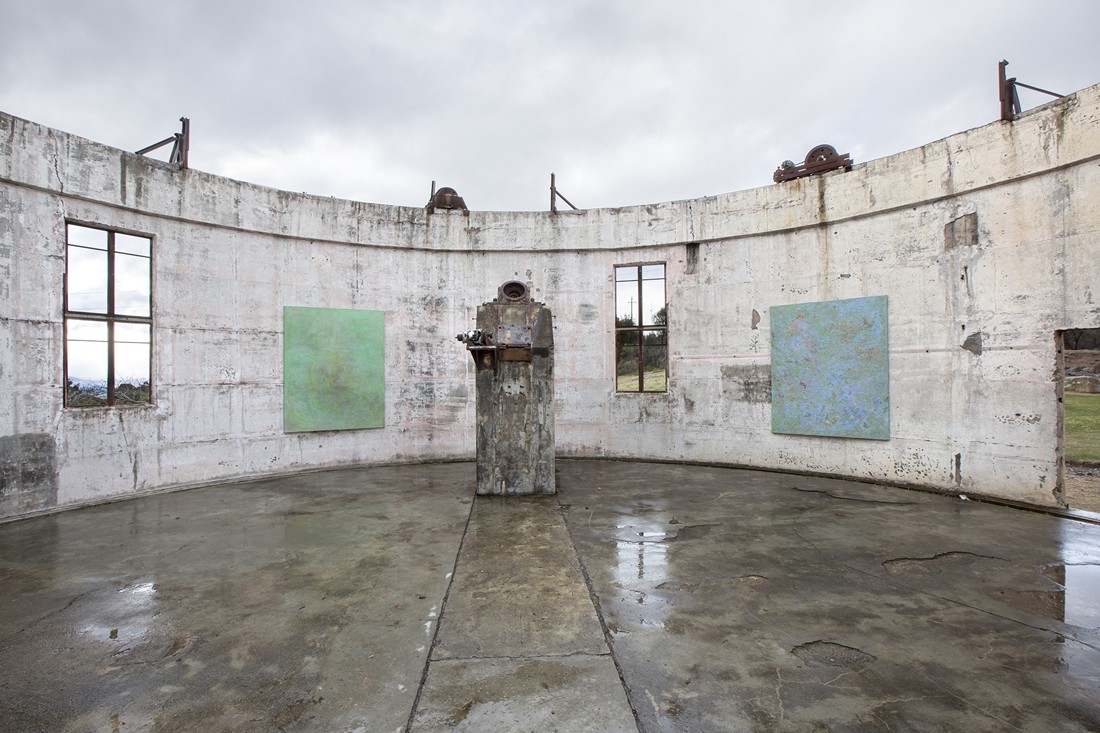

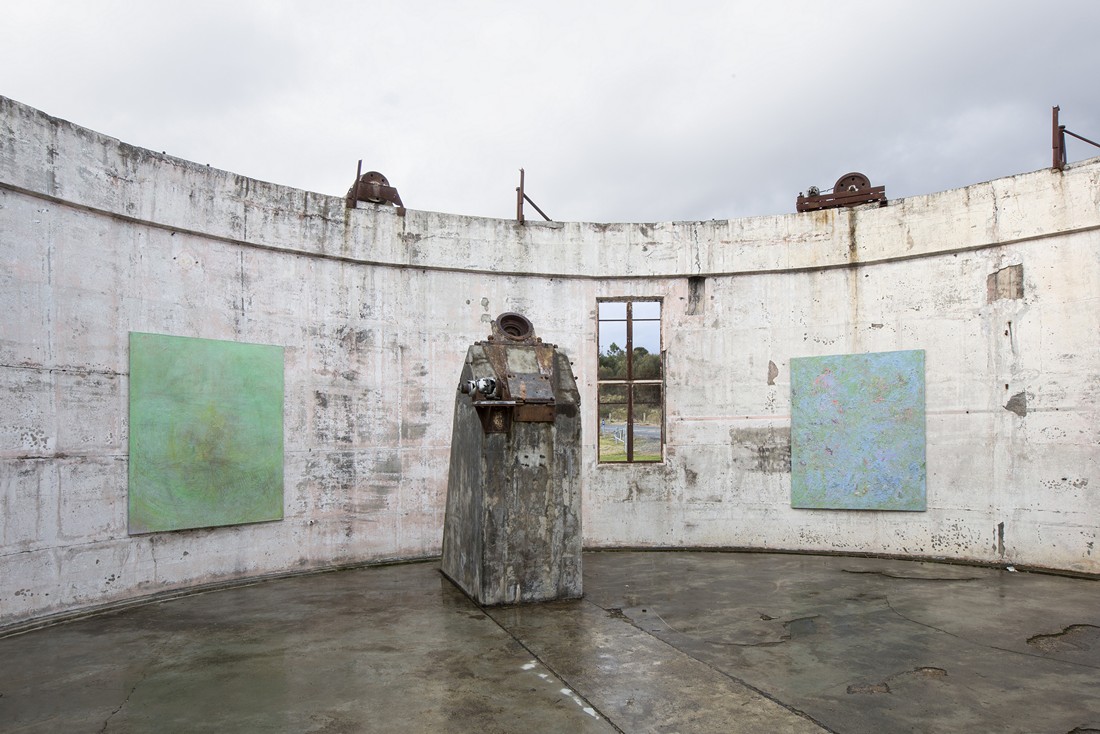

at Al Fresco, Yale-Columbia Telescope Ruin

Mount Stromlo, Kamberri/Canberr

“PANGS” reflects on the

degradation of the body (as spirit, as

physical vessel, as painting) brought

about through stress, and the more

impersonal forces that bring a heavy

weight to bear.

A ‘pang’ is anxiety arriving at speed

– being sharply felt but always

unexpected, it imposes upon

certitude the “weight of the world”,

the fundamental unknowingness of

being human, demanding that we

reckon with all that confronts us.

Pangs are the animating anxieties

that drive us to question and

continue, and that which drives

Luke to painting.

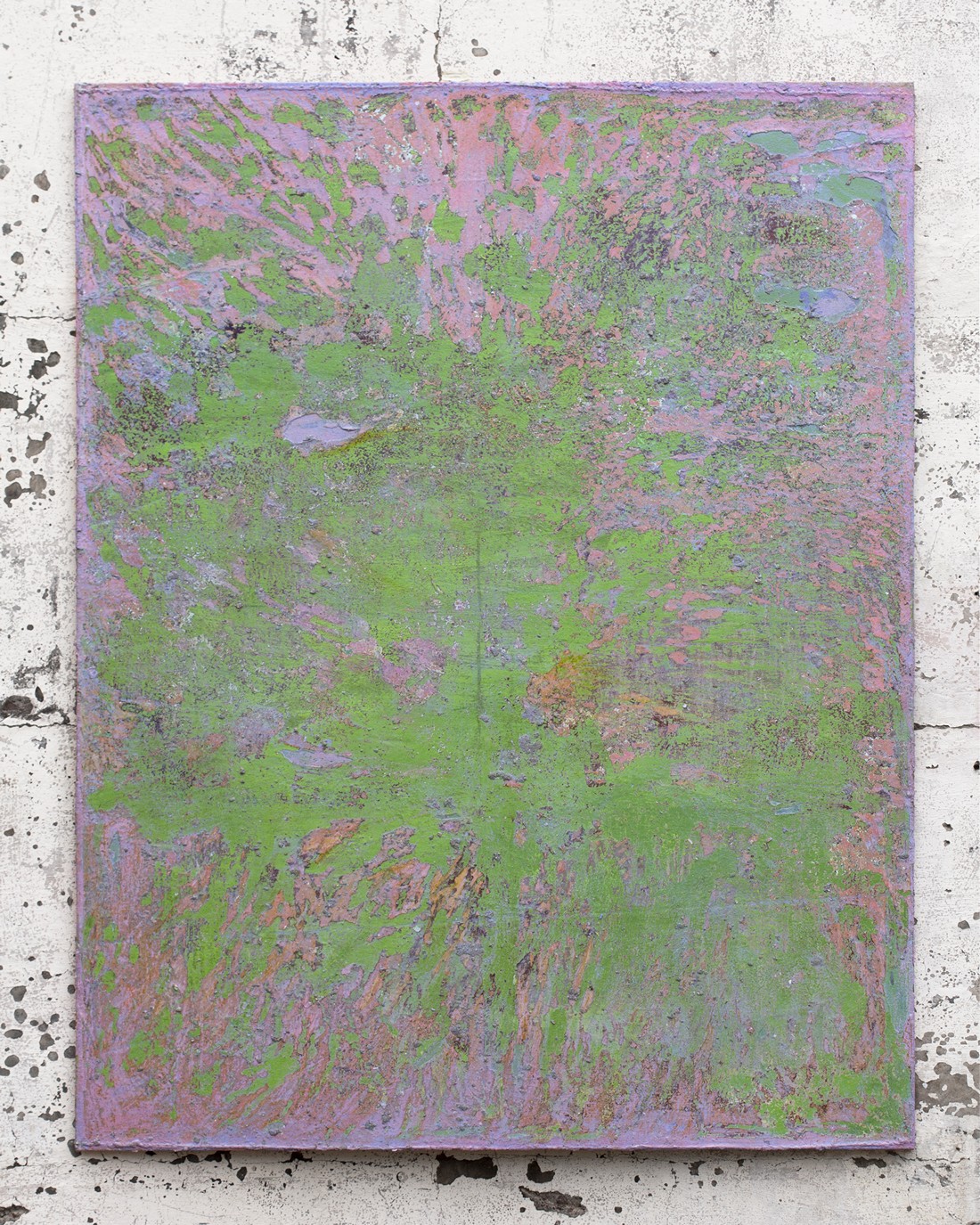

The four large canvases included in

this exhibition have haunted Luke

like an affliction, their accumulated

surfaces playing witness to a

hyper-curious and heavily-physical

engagement by the artist.

What we see is the effluence and

decay of these manic interactions:

the body of the painting firstly

nourished with attention and

energy, then flushed away. What

remains is the ordure (manifest as

muck, filth, shit, rubbish, pollution

and waste) of some internal anguish,

the emotional silt that has ultimately

settled in a fetid pool of physical

disorder, an organic continuum

fixed in a satin like skin set-hard

like mud in the sun – a “primordial

mud” – harbouring in its decay the

richness and precariousness of all

life.

“... When the waters retreated, a

deep layer of warm mud covered

the earth. Now, this mud, which

harboured in its decay all the

enzymes from what had perished in

the flood, was extraordinarily fertile:

as soon as it was touched by the

sun, it was covered with shoots from

which grasses and plants of every

type sprang forth; and, further, its

soft, moist bosom was host to the

marriages of all the species saved

in the ark. It was a time, never to be

repeated, of wild, ecstatic fecundity,

in which the entire universe felt

love, so intensely that it nearly

returned to chaos.

Those were the days when the

earth itself fornicated with the sky,

when everything germinated and

everything was fruitful. Not only

every marriage but every union,

every contact, every encounter,

even fleeting, even between

different species, even between

beasts and stones, even between

plants and stones, was fertile, and

produced offspring not in a few

months but in a few days. The sea

of warm mud, which concealed

the earth’s cold, prudish face, was

one boundless nuptial bed, all its

recesses boiling over with desire

and teeming with jubilant germs.

This second creation was the true

creation, because, according to

what is passed down among the

centaurs, there is no other way to

explain certain similarities, certain

convergences observed by all. Why

is the dolphin similar to the fish,

and yet gives birth and nurses its

offspring? Because it’s the child

of a tuna and a cow. Where do

butterflies get their delicate colors

and their ability to fly? They are

the children of a flower and a fly.

Tortoises are the children of a frog

and a rock. Bats of an owl and a

mouse. Conchs of a snail and a

polished pebble. Hippopotami of

a horse and a river. Vultures of

a worm and an owl. And the big

whales, the leviathans—how to

explain their immense mass? Their

wooden bones, their black and oily

skin, and their fiery breath are living

testimony to a venerable union in

which—even when the end of all

flesh had been decreed—that same

primordial mud got greedy hold of

the ark’s feminine keel, made of

gopher wood and covered inside

and out with shiny pitch.

Such was the origin of every form,

whether living today or extinct...”

— Primo Levi,

‘Quaestio De Centauris’, 2015